Presence and seasonal variation of trihalomethanes (THMs) levels in drinking tap water in Mostaganem Province in northwest Algeria

Keywords:

Analyse, Drinking water, Trihalomethanes, Seasonal variationAbstract

Background: The use of chlorine to disinfect water, produces various disinfection byproducts such as trihalomethanes (THMs). These compounds are formed when free available chlorine reacts with natural organic matter in raw water during water disinfection. Epidemiologic studies have shown an association between long-term exposure to THMs and an increased risk of cancer, all of them are suspected of having carcinogenic effects.

Aim: The aim of this study was to determine the presence of THMs in the drinking tap water of Mostaganem Province (Algeria) in order to assess the seasonal variation in trihalomethane levels in tap water and to identify the season of high risk to the consumer.

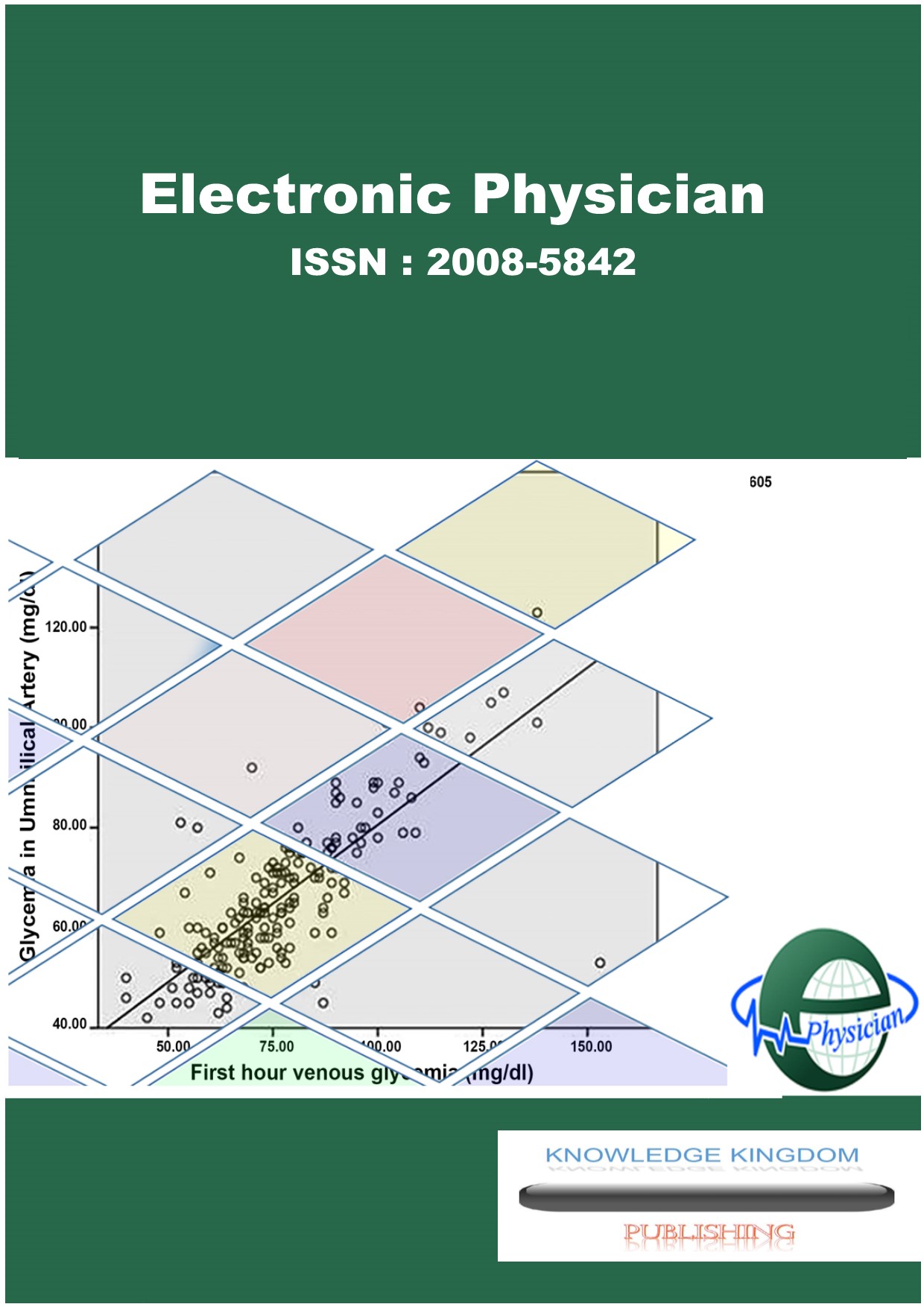

Methods: This analytical study was conducted in Mostaganem Province, Algeria in March, July, September and December 2015. Primarily, we proceeded to collect 30 samples from different areas of Mostaganem Province which were marked with a higher level of residual chlorine for the year 2015; secondly, we utilised the HS-SPME method for determination of trihalomethanes in drinking tap water over a period of four months. For comparison of trihalomethanes values, we used ANOVA.

Results: The results obtained show variability in total THM concentrations from one district to another, with a maximum of 198 μg/l recorded in the Achaacha district during July, but the lowest value 07.84 μ g/l is noted at Salamandre city during the same period, noting that these values decrease progressively during the winter period.

Conclusion: Our drinking tap water samples include a large quantity of THMs with different concentrations, where the dibromochloromethane and the bromoform constitute the major portion of THMs.

References

Rodriguez MJ, Serodes JB. Spatial and temporal evaluation of trihalomethanes in three water distribution

systems. Water Res. 2001; 35(6): 1572–86. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00403-6. PMID: 11317905.

Rook JJ. Formation of haloforms during chlorination of natural water. Water Treat Exam. 1974; 23(2):

-43.

Bellar TA, Lichtenberg JJ, Kroner RC. The occurrence of organohalides in chlorinated drinking waters. J

Am Water Works Assoc. 1974; 66(12): 703–6.

Lekkas TD. Haloforms and Related Compounds in Drinking Water. Berlin: Springer; 2003: 193–214. doi:

1007/978-3-540-44997-3_8.

Arthur CL, Pawliszyn J. Solid phase microextraction with thermal desorption using fused silica optical

fibers. Anal Chem. 1990; 62(19): 2145–8. doi: 10.1021/ac00218a019.

Stack MA, Fitzgerald G, O’Connell S, James KJ. Measurement of trihalomethanes in potable and

recreational waters using solid phase micro extraction with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Chemosphere. 2000; 41(11): 1821–6. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00047-3. PMID: 11057623.

Cho DH, Kong SH, Oh SG. Analysis of trihalomethanes in drinking water using headspace-SPME

technique with gas chromatography. Water Res. 2003; 37(2): 402-8. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00285-3.

PMID: 12502068.

Nakamura S, Daishima S. Simultaneous determination of 22 volatile organic compounds, methyl-tert-butyl

ether, 1, 4-dioxane, 2-methylsoborneol and geosmin in water by headspace solid phase microextraction-gas

chromatography-mass spectrometry. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2005; 548(1-2): 79-85. doi:

1016/j.aca.2005.05.077.

Cancho B, Ventura F, Galceran MT. Solid-phase microextraction for the determination of iodinated

trihalomethanes in drinking water. J Chromatogr A. 1999; 841(12): 197-206. PMID: 10371048.

Bahri M, Driss MR. Development of solid-phase microextraction for the determination of trihalomethanes

in drinking water from Bizerte, Tunisia. Desalination. 2010; 250(1): 414-7. doi:

1016/j.desal.2009.09.067.

Serrano A, Gallego M. Rapid determination of total trihalomethanes index in drinking water. J Chromatogr

A. 2007; (1-2): 26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.03.101. PMID: 17420023.

Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. 2nd Edition, Volume1, Recommendations. World Health

Organization. Geneva; 1993.

Health Canada. Chlorinated disinfection by-products (SPCD). 2000.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. National primary drinking water regulation: Disinfectants

and disinfection by products, final rule, In federal Register Parts IV(40 CFR Part 9,141 and 142 December

: 69390-69476.

Nieminski EC, Chaudhuri S, Lamoreaux T. The occurrence of DBPs in Utah drinking waters. J

AWWA.1993; 85(9): 98–105.

Lee KJ, Kim BH, Hong JE, Pyo HS, Park SJ, Lee DW. A study on the distribution of chlorination by- products (CBPs) in treated water in Korea. Water Res. 2001; 35(12): 2861–72. doi: 10.1016/S0043- 1354(00)00583-2. PMID: 11471686.

Ibarluzea JM, Goni F, Santamaria J. Trihalomethanes in water supplies in the San Sebastian area, Spain.

Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1994; 52(3): 411-8. doi: 10.1007/BF00197830. PMID: 8142713.

Singer PC, Obolensky A, Greiner A. DBPs in chlorinated North Carolina Drinking Water. J AWWA.

; 87: 83–92.

Durmishi H, Bujar D, Vezi M, Ismaili A, Shabani Sh, Abduli. Seasonal Variation of Trihalomethanes

Concentration in Tetova's Drinking Water (Part B). World J Appl Enviro Chem. 2012; 1(2): 42-52.

Souaya EMR, Abdullah AM, Mossad M. Seasonal Variation of Trihalomethanes Levels in Greater Cairo

Drinking Water. Mod Chem appl. 2015; 3: 149. doi: 10.4172/2329-6798.1000149.

Toroz I, Uyak V. Seasonal variations of trihalomethanes (THMs) in water distribution networks of Istanbul

City. Desalination. 2005; 176(1): 127-41. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2004.11.008.

Baytak D, Sofuoglu A, Inal F, Sofuoglu SC. Seasonal variation in drinking water concentrations of

disinfection by-products in IZMIR and associated human health risks. Sci Total Environ. 2008; 407(1):

–96. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.08.019. PMID: 18805568.

Vinette Y. Évolution spatio-temporelle et modélisation des trihalométhanes dans des réseaux de

distribution d'eau potable de la région de Québec. Mémoire du grade de maître ès sciences; Université

Laval. Canada. 2001: 157.

Patelarou E, Kargaki S, Stephanou EG, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Sourtzi P, Gracia E, et al. Exposure to

brominated trihalomethanes in drinking water and reproductive outcomes. Occup Environ Med. 2011;

(6): 438-44. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.056150. PMID: 20952554.

Sketchel J, Peterson HJ, Christofi N. Disinfection by product formation after biologically assisted GAZ

treatment of water supplies with different bromide and DOC content. Water Res. 1995; 12(29): 2635-42.

doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(95)00130-D.

Villanueva CM, Gagniere B, Monfort C, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Cordier S. Sources of variability in levels

and exposure to trihalomethanes. Environ Res. 2007; 103(2): 211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.11.001.

PMID: 17189628.

Aizawa T, Magara Y, Musashi M. Effect of bromide ions on trihalomethanes (THMs) formation in water.

Aqua. 1998; 3: 41.

Bond T, Huang J, Graham NJ, Templeton MR. Examining the interrelation ship between DOC, bromide

and chlorine dose on DBP formation in drinking water- a case study. Sci Total Environ. 2014; 470-471:

-79. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.09.106. PMID: 24176694.

Uyak V, Toroz I. Investigation of bromide ion effects on disinfection by-products formation and speciation

in an Istanbul water supply. J Hazard Mater. 2007; 149(2): 445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.04.017.

PMID: 17517472.

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2020 KNOWLEDGE KINGDOM PUBLISHING

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.