Assessment of unhealthy days among Iranian reproductive age women in 2012

Keywords:

Unhealthy days, Physical, Mental, Dysfunction, Women, Reproductive ageAbstract

Background: Unhealthy days are defined as the number of days during the past 30 days that a woman has not had a feeling of wellbeing. Wellbeing includes the woman’s judgments about the level of satisfaction and quality in her life. Assessment of a woman’s perception of unhealthy days can be used to help her determine the extent of the burdens associated with mental and physical feelings that things are not going well in her life, job and relationship. This study was conducted to measure unhealthy days and the general health status in Iranian women of reproductive age based on their own perceptions.

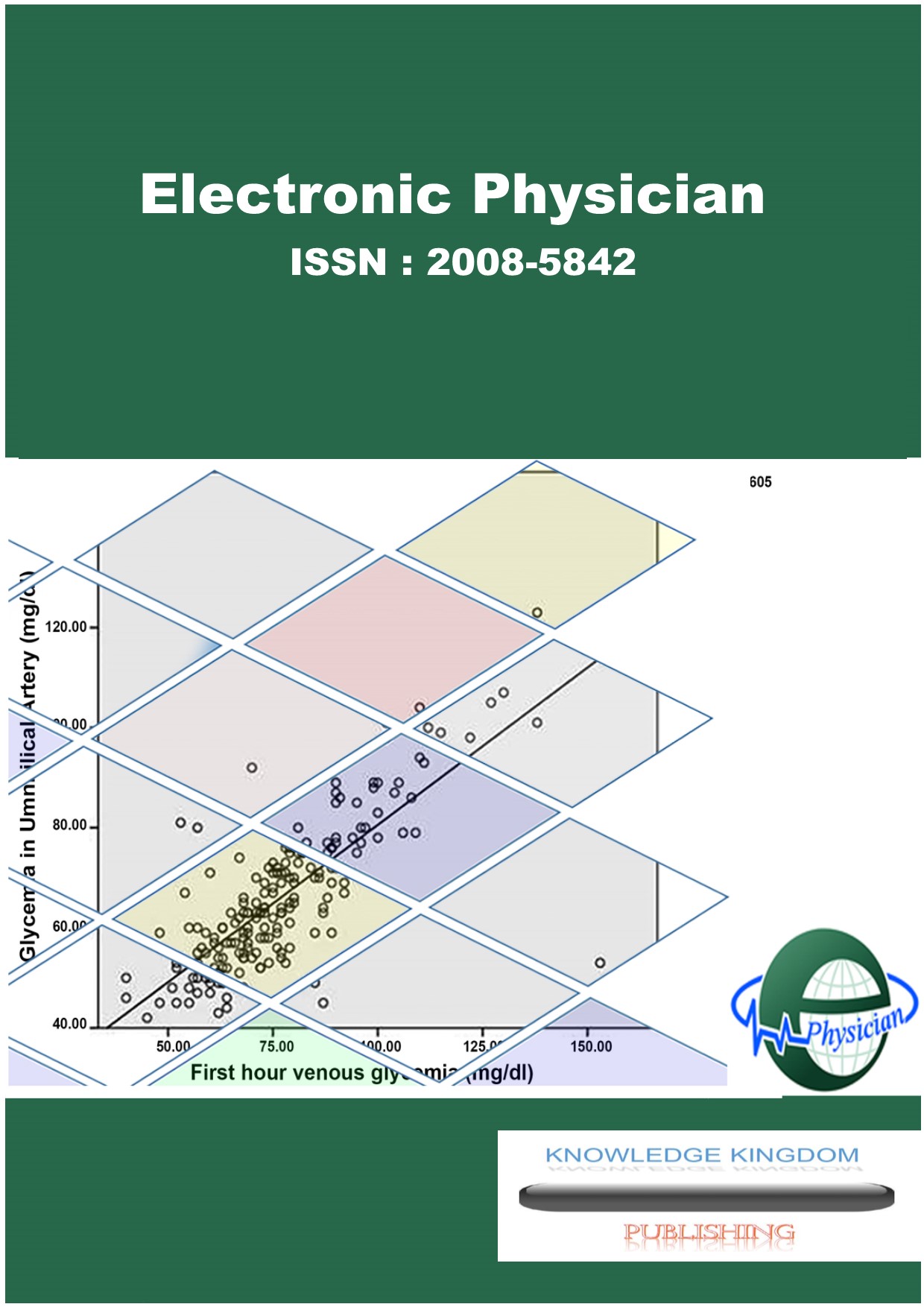

Methods: The participants of this study were women of reproductive age who were referred to health centers in Mashhad, Iran, in 2012. With the stratified random sampling method, 220 women were included in the study. The health-related quality of life-4 (HRQOL-4) questionnaire was used to assess the women’s self-perceived unhealthy days. The data that were collected were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis, chi-squared, Pearson correlation, and logistic linear regression tests with SPSS 11.5.

Results: The mean age of the participants was 32.6 years, and the median number of the self-perceived unhealthy days was 7.1 days (per month). In the domains of physical, mental, and disability unhealthy days, the data indicated 2 days, 2.1 days, and 0.1 day in a month, respectively. Also, nearly half of the participants reported that their general health status was poor to fair. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that there was a significant difference between unhealthy days in the different age groups (p=0.01) as well as for the physical (p=0.02) and mental domains (p=0.4). The results of the regression analysis showed that the number of physical unhealthy days increased with age, number of children, and education. The number of mental unhealthy days increased with age, and the number of disability days increased as the age at which they were married decreased (p<0.05). A significant inverse relationship was observed between physical unhealthy days and education, with the number of physical unhealthy days decreasing as the years of education increased (r=-0.19, p=0.005).

Conclusion: Women with less education who were older than 40, who married at an early age, and had more children reported more unhealthy days. These results emphasize the importance of preventive and educational health interventions in these vulnerable groups based on their physical and mental needs.

References

Talor, Ross V. Measuring healthy days: population assessment of health-realth quality of life. U.S.

department of health and human services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); November

Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf

Drum CE, Krahn G, Culley C, Hammond L. Recognizing and responding to the health disparities of people

with disabilities. Calif J Health Prom. 2005; 3(3):29–42. Available from:

http://echt.chm.msu.edu/BlockIII/Docs/RecRead/RecognizeRespond.pdf

Marcum JA. Humanizing modern medicine: an introductory philosophy of medicine. Netherlands:

Springer; 2008.

Galette CL, Hepstead K, Bresnitz EA. Healthy Days: Measuring the Health Related Quality of Life, New

Jersey 2003. NJ Department of Health and Senior Services-Center for Health Statistics. 2005. Available

from: http://nj.gov/health/chs/healthydays_0905.pdf.

Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Niakas D, Tountas Y. Health and Quality of Life. Health Qual Life

Outcomes. 2007; 5:55.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: a conceptual model of

patient outcomes. J Am Med Assoc. 1995; 273(1):59-65.

Artazcoz La, Borrell C, Benach J, Cortès I, Rohlfs I. Women, family demands and health: the importance

of employment status and socio-economic position. Social science & medicine. 2004; 59(2):263-74.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.029

Boldaji L, Foruzan A, Rafiey H. Quality of Life of Head-of-Household Women: a Comparison between

those Supported by Welfare Organization and those with Service Jobs. Soc Welf. 2011; 40:9-28.

Kerman SF, Montazeri A, Bayat M. Quality of life in employed and housewife women: a comparative

study. Payesh J. 2012; 1(41):111-6.

Moriarty DG, Kobau R, Zack MM, Zahran HS. Tracking healthy days—a window on the health of older

adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2 (3): A16. PMID: 15963318, PMCID: PMC1364525

Naserkhaki V BA, Hoseini S,Shogaee D, Naserkhaki L. Comparison of the quality of life of women and

men working in SAPCO. Health System Res. 2012; 2:290-300.

Zahran HS, Kobau R, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Holt J, Donehoo R, et al. Health-related quality of life

surveillance—United States, 1993–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005; 54(4):1-35. PMID: 16251867

Drum CE, Horner-Johnson W, Krahn GL. Self-rated health and healthy days: examining the “disability

paradox”. Disabil Health J. 2008; 1(2):71-8. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2008.01.002. PMID: 21122714

Downloads

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2020 KNOWLEDGE KINGDOM PUBLISHING

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.